Eighteenth Century Moroccan Diplomats

By Peter Kitlas in SNAP

May 1, 2021

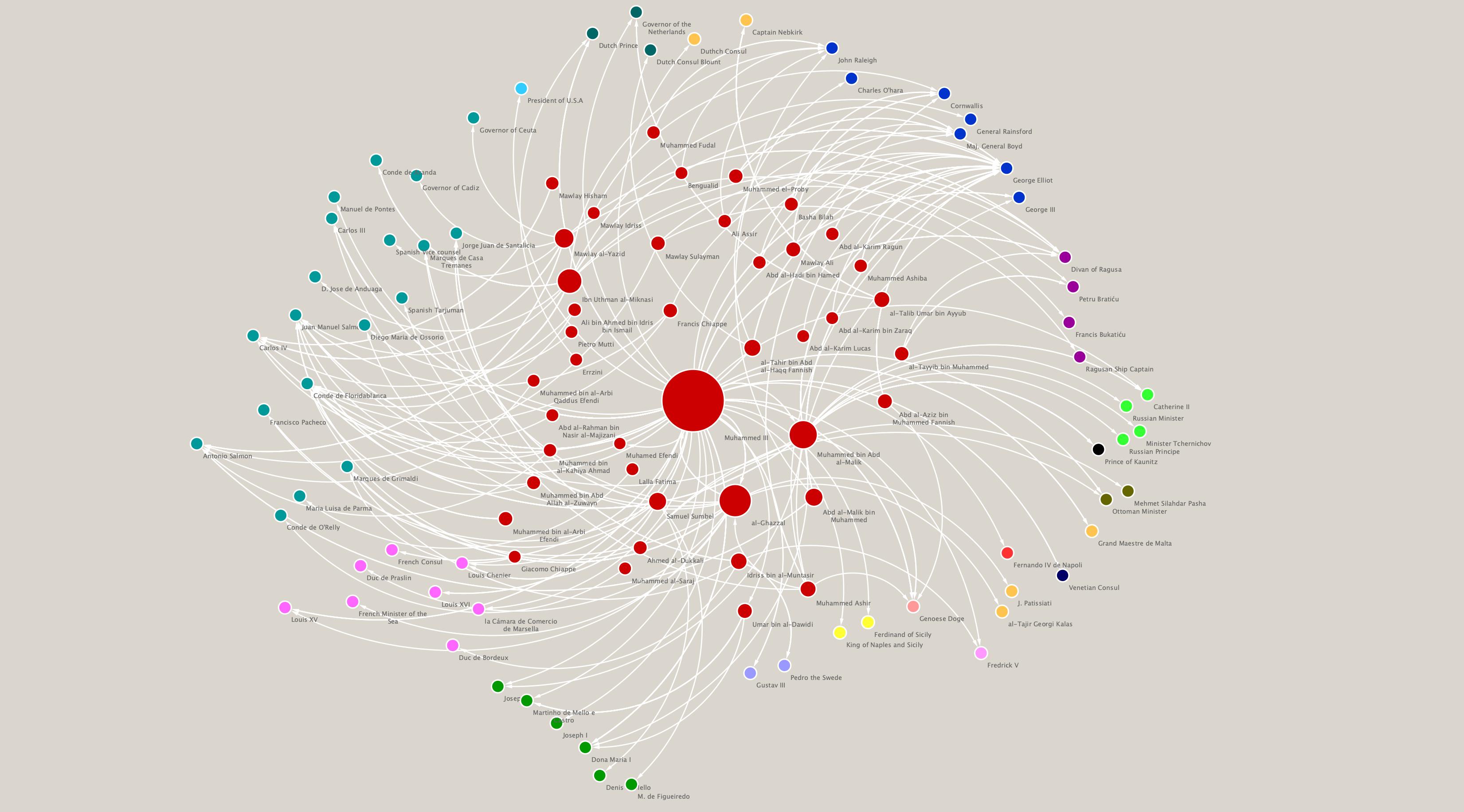

This is a new installment in which I attempt to visualize Moroccan diplomatic networks during the reign of Muhammad III (1757-1790) through an analysis of their correspondence. Using official letters collected from archives across the Mediterranean, this network analysis not only demonstrates the breadth and intensity of Moroccan diplomatic relations during the eighteenth century, but also seeks to reframe how we understand the internal mechanisms of Morocco’s diplomatic system. (A more detailed version of this is presented in my dissertation, “Divinely Guided Ambassadors: Ottoman and Moroccan Roots of Modern Diplomacy in the Eighteenth Century Mediterranean”)

The first iteration of this monthly series focuses on the Moroccan sultan himself, Muhammad III. Histories of eighteenth century Morocco often cite Muhammad III as one of the most influential characters in the creation of modern Morocco. He is noted both for unifying the country by quelling internal rebellions as well as opening up Morocco to a modernizing international trade and treaty system. Under his reign Morocco signed commercial and peace treaties with at least twelve countries across Europe as well as the nascent United States of America. He also is credited with planning and building the Atlantic port-city of Essaouira. In many respects, these aspects of his reign have centered nearly all studies of Moroccan diplomacy around the sultan. But what did Moroccan diplomacy actually look like in the eighteenth century?

Moroccan Diplomatic Correspondence in the 18th Century

Moroccan Diplomatic Correspondence in the 18th Century

The figure above represents all of the Moroccan diplomatic actors who wrote official diplomatic correspondence with foreign counterparts during the reign of Muhammad III. These Moroccan actors are marked in ‘Red’. Actors from other countries are labeled with the various colors. For instance, Spanish actors are marked in ‘Tourquoise’, French in ‘Pink’, British in ‘Blue’, Portuguese in ‘Green’, and Ragusans in ‘Purple’.

Furthermore,the size of each node is dictated by how many official diplomatic letters that Moroccan actor sent. In other words, the larger the node the more official diplomatic letters that person sent. If we zoom in on the larger map, a few things become clear:

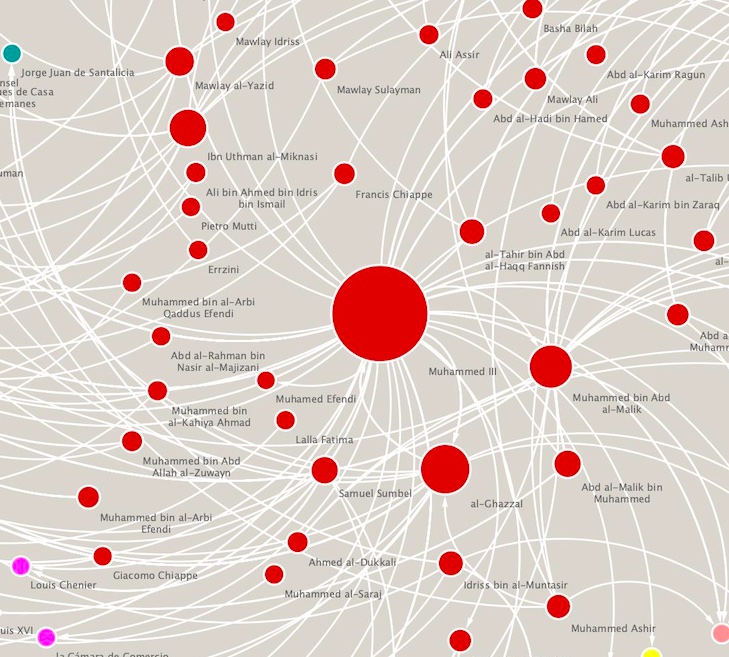

Zoom-in on the center of the entire network graph

Zoom-in on the center of the entire network graph

Here we get a better understanding of the relative size of the diplomatic nodes as well as the names of the individuals attached to each. Wading through all of the clutter, a few key names emerge. Unsurprisingly, the first of these is Muhammad III, whose node is much larger than anyone else in comparison. Aside from this we also find three other relatively active diplomats: al-Ghazzal, Muhammad bin Abd al-Malik, and Ibn Uthman al-Miknasi. These characters will be discussed in later posts. So for now, we will turn our attention to Muhammad III.

In many respects, this network analysis confirms his centrality to the Moroccan diplomatic system. His output is clearly higher than anyone else. But what exactly did this mean? Who was he corresponding with? And how often?

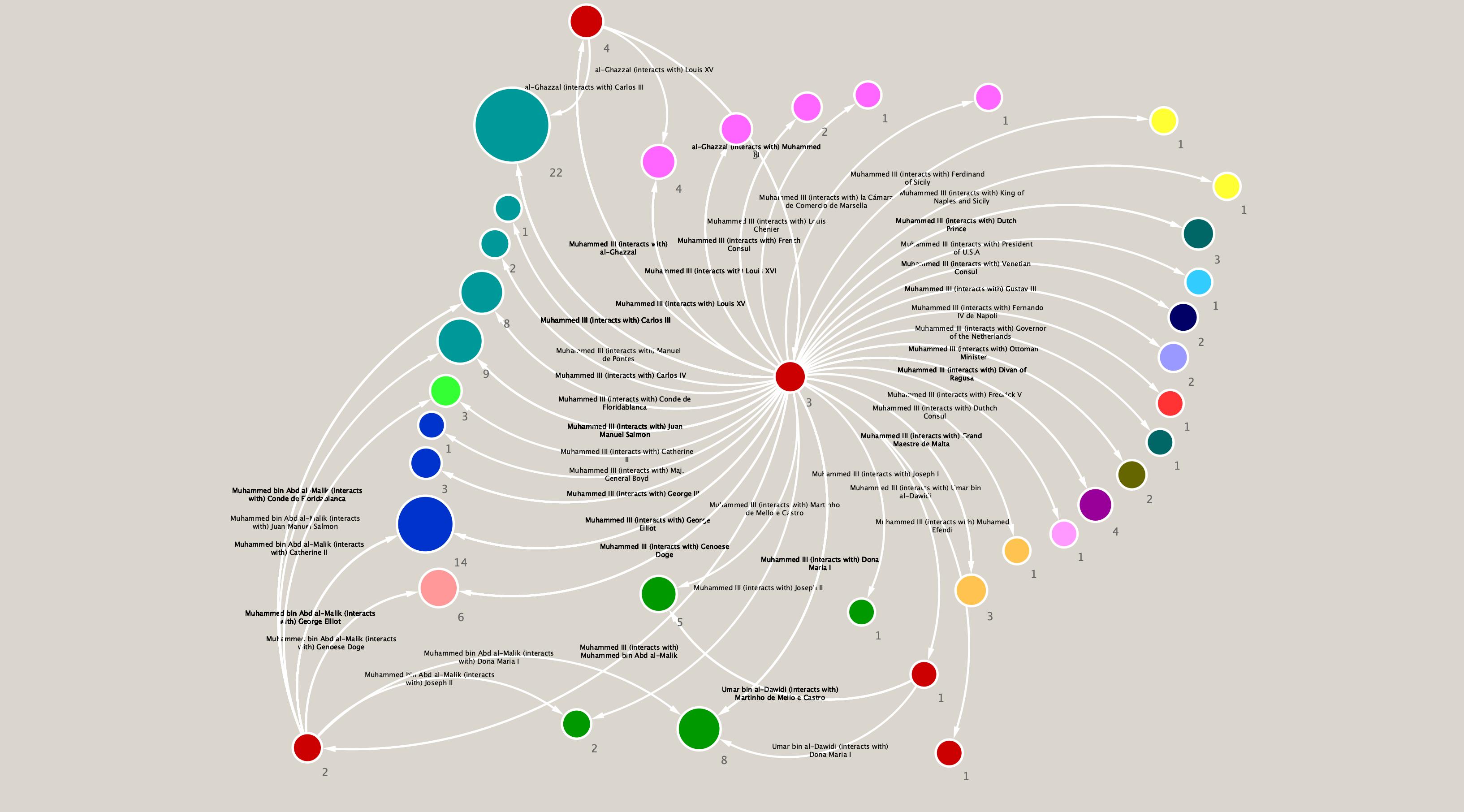

If we separate out Muhammad III’s connections from the rest of the Moroccan diplomatic actors a slightly different image of the Moroccan sultan’s diplomatic role emerges. Here, the network analysis graph is inversed. That is, a larger node indicates more letters received from the sender, Muhammad III.

An Isolated Graph of Muḥammad III’s connections

An Isolated Graph of Muḥammad III’s connections

What is immediately striking about Muhammad III’s graph is that, despite sending a large amount of letters, he mostly corresponds once or twice with foreign counterparts. If we place this within the context of a 30-year reign, one, two, or even three letters does not seem like very many. This is the first indication that his overtly prominent place in the broader graph does not demonstrate the actual nuance of his position relative to other Moroccan diplomats. While he might have been directing the broad contours of Moroccan policy during this time period, this graph suggests that there were other actors who were taking care of the day-to-day operations of diplomacy.

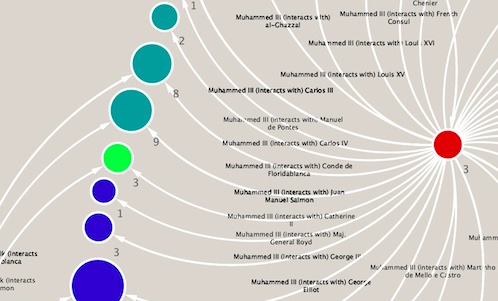

There are, of course, some larger nodes in Muhammad III’s graph. These include Carlos III of Spain and George Elliot of Gibraltar.

Zoom in on Muḥammad III’s connections

These are Morocco’s closest neighbors so it is not a surprise that Muhammad III had more consistent contact with them. Nevertheless, the numbers are still relatively small with 22 to Carlos III and 14 to George Elliot. As we will see in later posts, these are numbers that were easily surpased by other Moroccan diplomatic actors in much shorter periods of time.

As such, this brief examination of the relative diplomatic network of Muhammad III helps us to de-center our study of Moroccan diplomacy from the sultan. Yes - he certainly helped to direct the broad contours of Moroccan diplomatic policy. But, as the graph indicates, he was not necessarily involved in the day-to-day practice. This conclusion opens up an important space to focus on the practices, thoughts, and influences of other Moroccan diplomatic actors.

Muhammad III’s graph provides a bit of a teaser for the next installment, which will dive deeper into these individuals. That is, in addition to the foreign counterparts, four Moroccan actors appear in his network. This indicates direct correspondence between the Moroccan sovereign and his diplomats. These connections, which have not been detailed before, will be the subject of the next post. In it, we will attempt to build a better understanding of the local, institutional characteristics of diplomacy in Muhammad III’s court. For now, however, here is a photo of the beautiful Middle Atlas cedars from Jebel Bouiblane followed by a short bibliography.

Middle Atlas Cedars from Jbel Bouiblane

Bibliography:

-

Harrak, Fatima. 1989. “State and Religion in Eighteenth Century Morocco: The Religious Policy of Sidi Muhammad b. ’Abd Allah, 1757-1790.” London: SOAS.

-

Ibn ʿAbdallāh, ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz. 1985. al-Safāra wa-l-sufarā’ bi-l-Maghrib ʿabr al-tārīkh. Rabat: al-Maʿhud al-waṭanī li-l-dirāsāt.

-

Jādūr, Muḥammad. 2003. “al-Diblūmāsiyya al-Saʿdiyya, al-diblūmāsiyya al-ʿAlawiyya, istimrāriyya um qaṭīʿa: Aḥmed al-Manṣūr wa al-Mawlāy Ismāʿīl numūdhajan.” In al-Tārīk̲h wa-al-diblūmāsiyya: qaḍāyā al-muṣṭalaḥ wa-al-manhaj, edited by ʻAbd al-Majīd Qaddūrī, 223–53. Rabat: Jāmiʻat Muḥammad V.

-

Lourido Díaz, Ramón. 1989. Marruecos y el mundo exterior en la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII: Relaciones politico-comerciales del sultan Sīdī Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh (1757-1790) con el exterior. Madrid: Dispograf.

-

Miller, Susan Gilson. 2013. A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

-

Qaddūrī, ʻAbd al-Majīd.2003. al-Tārīkh wa-al-diblūmāsiyya: qaḍāyā al-muṣṭalaḥ wa-al-manhaj. Rabat: Jāmiʻat Muḥammad V.

- Posted on:

- May 1, 2021

- Length:

- 5 minute read, 1042 words

- Categories:

- SNAP

- Tags:

- Network Analysis

- See Also: